The Korean Peninsula is composed of various geological strata formed in different eras. Some layers date back billions of years, while others were formed during the age of the dinosaurs, and still others after the extinction of the dinosaurs. By examining these strata, we can learn about the many changes that have taken place on the Korean Peninsula—such as when it was divided into two landmasses, submerged under the sea, or connected to the Japanese archipelago. The geological environment and fossils of the peninsula reveal this rich history.

However, there is a particular geological period whose sedimentary layers cannot be found anywhere in South Korea. That is the Paleogene period of the Cenozoic era, which includes the Paleocene, Eocene, and Oligocene epochs. In South Korea, the Cenozoic sedimentary layers that remain were mostly formed after the Neogene period, around 20 million years ago. The sedimentary layers along the east coast, as mentioned earlier, are from this more recent time.

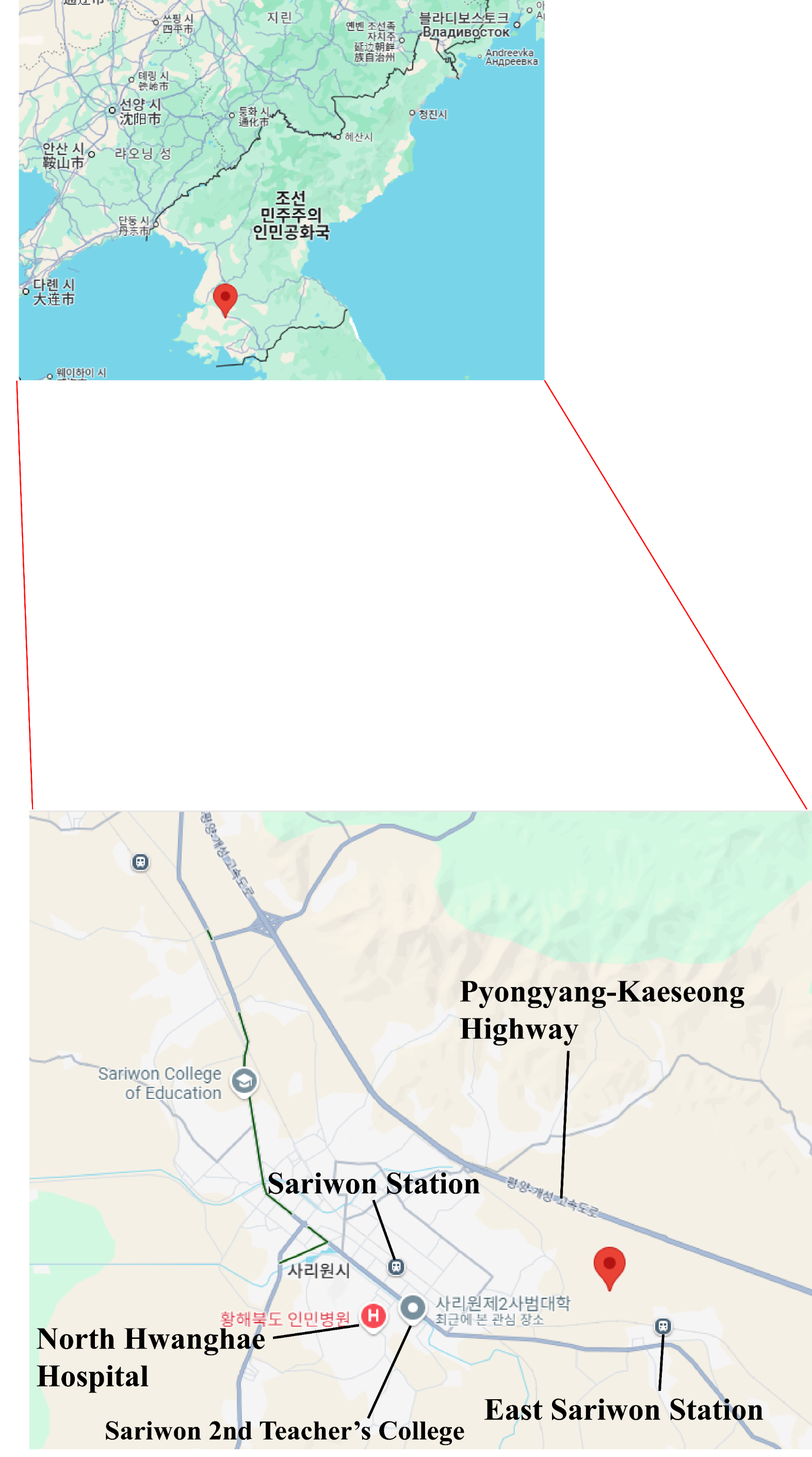

But if we shift our focus to North Korea, the story changes somewhat. In a few regions of North Korea, sedimentary layers from the Paleogene period of the Cenozoic era still remain. These include the Sariwon Basin in Sariwon City, North Hwanghae Province, and the Anju Basin in Anju City, South P'yŏngan Province. These two areas are the only places on the Korean Peninsula where fossils from the Paleogene period have been discovered.

In particular, during the Japanese colonial period, mammal fossils were reportedly discovered in the Sariwon Basin. These fossils were found in a coalfield located in present-day Pongsan County, Hwanghae Province. This coalfield is known as the Pongsan Coalfield (鳳山炭田). During the colonial era, it was referred to by its Japanese pronunciation, Hosan Coalfield. In this article, we will explore the only known Paleogene mammal fossils of the Korean Peninsula, which were excavated and studied by Japanese researchers during the colonial period.

(1) Pongsan Coalfield

The sedimentary layer in which the Pongsan Coalfield is located lies above the Sangwon System, a geological formation from the late Proterozoic era—formed roughly between 1 billion and 540 million years ago. This ancient layer is covered at the top by gravel deposits from the Holocene epoch of the Quaternary period, which means it was formed in relatively recent, modern times. Therefore, the coalfield consists of sedimentary layers that lie between these two extremes: ancient rock from about 1 billion to 540 million years ago, and modern gravel layers from today.

The Pongsan Coalfield is located to the east of a plain through which the Jaeryeong River, a tributary of the Taedong River, flows. Today, this area belongs administratively to Pongsan County, Sariwon City, in Hwanghae Province. According to North Korean geological studies conducted after Korea’s liberation from Japanese rule, the sedimentary formation that constitutes the Pongsan Coalfield was named the Osu Formation.

The primary type of coal produced in the Pongsan Coalfield is lignite. Lignite is a type of coal that contains more than 66% moisture and is typically used for domestic or fuel purposes. Lignite is also found in South Korea, such as in the Pohang area.

The Pongsan Coalfield was first discovered during the Japanese colonial period. It was around 1913—during the early years of Japanese rule and toward the end of the Meiji era in Japan—when a coal deposit was accidentally discovered during construction work in the Hwanghae Province region. Mining operations at the site began in 1922. According to records from 1935, about 100,000 tons of coal were extracted annually from the Pongsan Coalfield.

(2) The First Discovery of Mammal Fossils in the Pongsan Coalfield

During the Japanese colonial period, fossils of leaves and mollusks were excavated from the Pongsan Coalfield. Among these, the most notable finds were the fossils of mammals. The existence of mammal fossils in the Pongsan Coalfield was first reported in 1926. A geologist named Shintaro Nakamura introduced fossils belonging to the rhinoceros family that had been unearthed at the site.

According to Nakamura’s research, fossilized teeth, jawbones, and parts of leg bones from a rhinoceros species were discovered. He identified these remains as belonging to Chilotherium, a genus of rhinoceros that had been reported in China in 1924.

Unfortunately, Nakamura did not provide a detailed description of the fossils' morphology, and the specimens’ current whereabouts are unknown. Not even photographs of the fossils have survived, which is a regrettable loss for paleontological research.

In 1926, the fossil of Chilotherium was first reported, and around the same time, Professor Shigeyasu Tokunaga (徳永重康) of Waseda University excavated a fragment of a rhinoceros jawbone from the Pongsan Coalfield. He named it Aceratherium makii. He also argued that the Pongsan Coalfield belonged to sedimentary layers formed during the Miocene epoch of the Neogene period in the Cenozoic era. However, later discoveries revealed that some of the additional mammal fossils resembled those of mammals that lived during the Eocene epoch of the Paleogene period in Inner Mongolia.

The first scholar to formally describe the mammal fossils found in the Pongsan Coalfield was Professor Fuyuji Takai (高井冬二) of Tokyo Imperial University (now the University of Tokyo). He was given access to the Aceratherium fossils discovered by Professor Tokunaga, as well as other privately held fossil specimens, and published the results of his research in 1939.

During the Japanese colonial period, a total of 53 mammal fossil specimens were discovered. Unfortunately, many of these specimens have since been lost or their whereabouts are unknown. The remaining fossils are reportedly housed at the University of Tokyo.

(3) Mammal Fossils of the Pongsan Coalfield

[1] Brontotheriidae of the Pongsan Coalfield

Brontotheriidae were large, herbivorous mammals related to horses and rhinoceroses that lived during the Paleogene period of the Cenozoic era. Their fossils have been found in North America, the Middle East, and Asia. The discovery of Brontotheriidae fossils in the Pongsan Coalfield suggests that some of these animals may have expanded their range into the Korean Peninsula.

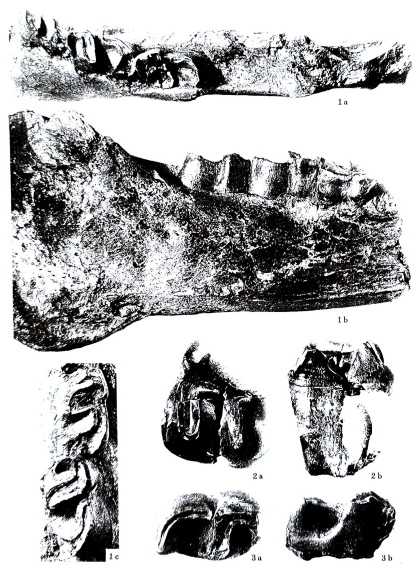

Professor Takai was the first to report the presence of Brontotheriidae in Pongsan. In 1939, he described fossilized tusks, molars, and parts of a jawbone that he had studied and concluded that they belonged to a species of Protitanotherium—a genus previously discovered in the United States. He classified the Korean specimens as Protitanotherium koreanicum.

However, this name (Protitanotherium koreanicum) later became invalid following subsequent re-evaluation. Because the fossils were too fragmentary, doubts were raised about whether it was appropriate to classify them as Protitanotherium in the first place.

A study published in 2004 reclassified the fossils as being closer to a mammal known as Protitan. On the other hand, a 2008 study suggested that the tooth fossils might actually be a mixture of teeth from several different mammal species.

Matthew C. Mihlbachler, a researcher at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, reviewed the taxonomy of Brontotheriidae and argued that the so-called Protitanotherium fossils more closely resemble the teeth of Diplacodon elatus and Pachytitan ajax. Although there are differing opinions on how these fossils should be classified, the current academic consensus is that the name Protitanotherium koreanicum, first proposed by Professor Takai, is no longer considered valid.

[2] Rhinoceros relatives of the Pongsan Coalfield

I previously mentioned Aceratherium makii, a species first reported by Professor Tokunaga in 1926. In 1929, he reclassified the specimen as a now-extinct species of modern rhinoceros (Rhinoceros), though he did not explain his reasoning.

In his 1939 study, Professor Takai reclassified the fossil once again. Based on the morphology of the molars, he argued that the specimen more closely resembled Caenolophus, an animal discovered in Inner Mongolia, rather than Aceratherium. However, subsequent studies concluded that while the teeth might appear similar, the evidence was insufficient to make a definitive classification. As a result, a question mark was added to the genus name.

Thus, the mammal fossil originally named Aceratherium makii is now classified as Caenolophus? makii.

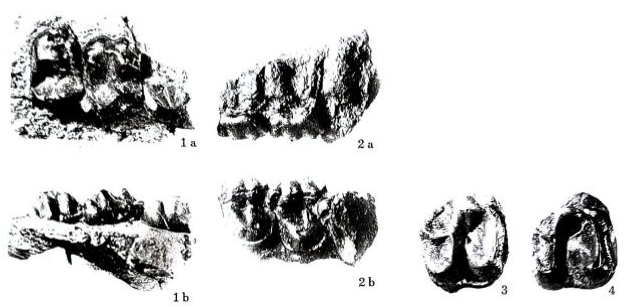

[3] Tapir relatives of the Pongsan Coalfield

Fossils of animals related to tapirs have been discovered in the Pongsan Coalfield. While tapirs today are found in South America, evidence suggests that from around 20 million years ago up until the Ice Age, they also lived in Europe, Asia, and North America. In other words, tapirs were once widespread across various regions of the world until relatively recently.

The tapir relatives discovered at Pongsan were originally classified as a different group of perissodactyl mammals but were later reclassified under the superfamily Tapiroidea (tapir-like animals). Two species of Tapiroidea have been identified from the Pongsan Coalfield: Colodon hodosimai and Plesiocolopirus grangeri.

Of these, two molars belonging to Plesiocolopirus grangeri were reclassified just one year before Korea’s liberation(1944) as belonging to another tapirid mammal named 'Cristidentinus', which is now considered as a subjective synonym of the genus Deperetella. However, the current whereabouts of these fossils are unknown. Professor Takai explicitly noted in his paper that the position of the specimen is“unknown.”.

[4] Mesonychids of the Pongsan Coalfield

In 1943, another mammal fossil from the Pongsan Coalfield was reported to the academic community. Tokio Shikama (later appointed professor at Yokoyama National University), then a researcher at Tohoku University, discovered fossils of a mesonychid—an extinct order of mammals distantly related to whales.

Although only a few tooth fossils were found, their morphology led Shikama to conclude that they belonged to a species of Harpagolestes, a genus within the Mesonychid order. He named the species Harpagolestes koreanicus. However, later research on the distribution of mesonychids in East Asia raised doubts about whether these fossils truly belonged to Harpagolestes. The primary issue was the extremely fragmentary nature of the fossils—only a few isolated teeth were recovered—making accurate classification difficult. Unfortunately, the fossil of Harpagolestes koreanicus, whose identity remains uncertain, is currently considered missing.

On this article, I had introduced the researches on mammalian fossils discovered in the Pongsan Coalfield. In addition to mammals, fossils of various plants and mollusks have also been found in the coalfield. According to Japanese researchers, these fossils appear to be similar in type to those found in China and Japan from comparable geological periods.

Since Korea's liberation, no new mammalian fossils seem to have been discovered in the Pongsan Coalfield. This conclusion is based on materials published by North Korea, which report no newly discovered mammalian fossils since the Japanese occupation (although plant and mollusk fossils have been reported post-liberation). It’s possible that more complete mammalian fossils remain undiscovered somewhere in the Pongsan Coalfield or the Sariwon Basin. Unfortunately, because the Sariwon Basin is located within North Korean territory, South Korean researchers are currently unable to conduct excavations or research in the area... Hopefully, peace will come to the Korean Peninsula soon so that free and open scientific research can be conducted.

Reference

Granger, W., Gregory, W. K., & Osborn, H. F. (1943). A revision of the Mongolian titanotheres. American Museum of Natural History.

Matsushita, S., Onoyama, T., & Maejima (1935). Geology and fossils of the Hosan Coalfield, Kokaido, Chosen. Chikyu, 23(6), 403–420. (In Japanese)

Mihlbachler, M. C. (2008). Species taxonomy, phylogeny, and biogeography of the Brontotheriidae (Mammalia: Perissodactyla). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 2008(311), 1–475

Nakamura, S. (1926). Geology of Hosan Coalmine in Hosan-gun, Kokai-do, Korea. Chikyu, 5(1), 97–98. (In Japanese)

Russell, D. E. (1987). The Paleogene of Asia: mammals and stratigraphy. Mémoires du Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle, Sciences de la Terre, 52, 1–488.

Shikama, T. (1943). A new Eocene creodont from the Hosan coal-mine, Tyosen. Bulletin of the Biological Society of Japan, 13(2), 7–11.

Szalay, F. S., & Gould, S. J. (1966). Asiatic Mesonychidae (Mammalia, Condylarthra). Bulletin of the AMNH; v. 132, article 2.

Takai, F. (1939). Eocene mammals found from the Hosan Coal-field, Tyosen. Journal of the Faculty of Science Imperial University of Tokyo series II, 5(6), 199–217, pls. 1–5.

Takai, F. (1944). Eocene Mammals from the Ube and Hosan Coal-fields in Nippon. Proceedings of the Imperial Academy, 20(10), 736–741.

Tomida, Y., & Lee, Y. N. (2004). A Brief Review of the Tertiary Mammals from Korean Peninsula (Part Two Natural History Studies). National Science Museum Monographs, 24, 197–206.

https://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Article/E0025552 (Encyclopedia of Korean Culture: Sariwon Coalfield)

'Fossils of Korea' 카테고리의 다른 글

| Dinosaur Skin impression in South Korea (0) | 2025.03.15 |

|---|---|

| Proboscidean fossils found in the Korean Peninsula (0) | 2025.03.12 |